Through What Door?

SJF • Lent 1b • Tobias S Haller BSG

God waited patiently in the days of Noah, during the building of the ark, in which a few, that is, eight persons, were saved through water. And baptism, which this prefigured, now saves you.

My friend Peter — named for the saint, of course — entered into Christ through a little blue door. He came to Columbia University in the late sixties as a graduate student, with the usual doubts and hopes of young men of that age, and that time and that place. People were saying that God was dead — yet the church still seemed to have some utility. The civil rights struggle showed the church was still one of the few things still alive and kicking against a world whose heart it seems had grown cold.

Peter was an intelligent young man, with a passion for justice and civil rights, and a cultured taste in art and music — he was studying medieval literature. But he wanted to learn more about the church before he got too involved with this whole “religion” thing.

And so he called on his neighborhood parish church, which, if you know Columbia will know just happens to be the Cathedral Church of St John the Divine. Given his intellect, passion for civil rights, and his taste for art, the choice was natural: the Episcopal Church was considered “the thinking person’s church” and the Cathedral leaders had taken a strong stand for civil rights, at the cost of a few wealthy donors. And there was no denying the beauty of that building, even in its unfinished state — and it’s still unfinished fifty years later!

Peter called the and they connected him with Canon West, who, the receptionist thought, would be the best person to talk with him about religion. Peter found Canon West much too busy to see him that week, but West told him that if he would come to the little blue door he would find half-way up the cathedral on the southern side at about 10:45 next Sunday morning he might have some time to talk with him about religion.

Peter had come of age in a culture that had forgotten what it is that goes on in cathedrals on Sundays at about 10:45, so he was caught short went through that little blue door into that cavernous space and asked for Canon West. Before he knew what was happening, he was whisked into the sacristy; many helping hands vested and girded him and dressed him up in an acolyte’s outfit, then handed him a one of the massive crucifixes that they use there at the Cathedral — and they weigh about 70 pounds! — and pushed him towards the head of a procession, maintained in place by Canon West’s stern eye and finger-snaps, and the nods, gestures and elbows of more experienced servers at the altar.

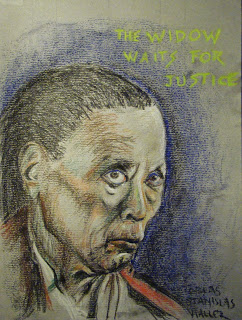

Peter was confused, but also furious, but he dared not challenge the imposing Canon West — with his bald head, black goatee and long black cape, who knows what powers might be at his disposal? Even had he dared, before he could protest, he was swept up in the worship — right at the head of the procession, along with at least three more crosses behind him, along with the embroidered banners that emerged from clouds of incense, floating like the masts and sails of ancient dream-ships navigating the valleys of those towering rough-hewn rock columns and walls. The roar of the organ resounded in the caverns of that space, the waves and wash of breakers of sound resounded and echoed back and forth — after all, the Cathedral is an eighth of a mile long; ranks of choristers and clergy in vestments ancient and modern, gloriously colorful, gold and scarlet; and there was Peter right in front — just behind the man with the incense-pot swinging and twirling the prayers of the saints up and up into that now invisible dome — and the congregation bowing in waves as he passed with that cross, as if pressed down by the weight of glory he was carrying.

And all the while all he could think was, “I’ll kill him!”

When the worship ended, as he was hanging up the borrowed vestment, still quivering with rage and disorientation, Canon West came up behind him, and laid a bony hand on his shoulder. The old priest spun him around, fixed him with a stern look, out from underneath those bushy eyebrows, and said, “Now, my boy, I’m prepared to talk to you about our religion.”

+ + +

Lent is upon us, a time in the church year when we raise the intensity a notch in our efforts to think about our religion. I’m sure all of us here could tell a tale about how we got here — through what little blue door each of us passed to enter the ark of salvation. That’s what it is, you know, this church of ours. It was prefigured, as Saint Peter tells us, in the ark in which Noah and his family were kept safe amidst the waters of the flood. Our church is an ark. As I have pointed out before, churches are often built like upside-down boats: if you look up to our ceiling there, in that part of the church called the “nave” — which also betrays its naval origins — you’ll see that the ribs of a boat’s hull have become the ribs that hold up our roof.

Each of us could tell how we boarded this upside-down boat, through what little blue — or red — door — even if we were carried in kicking and screaming when we were just a few weeks old. And yet here we are, the company of the baptized, some of you baptized right here in this font — I know, because I was the one that did it! We are gathered here together in this boat, a boat that has no first or second class passengers, no steerage for the poor, nor staterooms for the rich — but just one big lifeboat!

+ + +

It may seem strange to start the season of Lent with Scriptures all of which refer to baptism either directly or figuratively — since by tradition Lent is the one time of the year during which baptisms are not performed! But Lent anciently was the time when people were prepared for baptism at Easter; it was during these weeks that they studied, and fasted, and prayed to be ready to be baptized at the Great Vigil of Easter. And so we begin our Lent reminded of baptism, and of the fact that the church — this church, not just the building, not just the upside-down boat, but we the people are the company of the baptized, and it is worth reflecting on what it means to be on board this boat — and to reflect on where this boat is heading.

So this year, I want to use our Lent together to focus on what it means to be the church — this gathering of people who have been through the little blue door, a little red door, who have been washed in the waters of baptism, and fed with the bread of heaven. For this is how it begins, my friends — in the church as the ark of salvation. Now, some might be tempted to ask, “Isn’t there salvation outside the church?” well, it is not for me to speculate on God’s grace, or to place limits upon it. God can and will save whomever and however God pleases to do so. Is there salvation outside the ark of the church, outside the lifeboat? I hope so — there may be some good swimmers out there! But I know that there is salvation inside the ark of the church, inside the lifeboat; and it is my calling and my task — as it is yours, my friends — to gather up people floating out there in life jackets before they freeze to death!

We will not do this merely by talking to them about religion — there is plenty of talk about religion out there, my friends, and much of it probably keeps people away from church rather than bringing them to it. No, the answer is to invite them here, through our little red door, into this lifeboat, the one we know, where we can hear words about religion — but more importantly be dressed in a new garment, given a cross to bear, hear the music and the song and join in it too, and be fed with the bread and nourished with the wine, and not just hear words about God but give thanks to the Word of God — Jesus the Christ.

This is the Gospel Cruise my friends: the ark of salvation right on the corner of Jerome Avenue and 190th St in the Beautiful Bronx — as unbelievable and specific as God being born in a stable, and as wonderful and as gracious as being pulled from freezing water into a lifeboat.

This is where it all starts my friends — there will be time to talk about it later; but those who want assurance of salvation will first come on board.

When they have gone through the little door, blue or red, been clothed anew with the garment of baptism, and have carried the cross while rows of their sisters and brothers bow in reverence to the powerful symbol of the unspoken and unspeakable Word above all words and worlds — then, as Canon West said, there will be time to talk about our religion.+