Unexpected Good

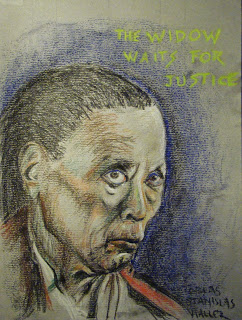

Proper 15a 2014 • SJF • Tobias Stanislas Haller BSG

Joseph told his brothers, “Do not be distressed, or angry with yourselves, because you sold me here; for God sent me before you to preserve life.… So it was not you who sent me here, but God.”

Some years ago, Rabbi Harold Kushner wrote a book called, When Bad Things Happen to Good People. This was not a book written from the dispassionate standpoint of a scholar and teacher. Rabbi Kushner was dealing with a personal tragedy as well — the death of his own young son. Even had he not experienced such a tragedy in his own family, he would not have needed to look very far to see many examples of bad things happening to good people. All you have to do is turn on the TV news to see plenty of examples of such tragedies. There is a whole subsection of theology dealing with just this question and I could go on and preach a couple of dozen sermons on the topic.

But for today I want to take a different approach and look at a different question, the opposite question: Why do good things happen to bad people? And I do that because of the continuation of the story that we heard this morning from the book of Genesis. We heard the start of Joseph’s story last week — how his brothers, jealous of their father’s affection, were on the point of murdering him; and how a sequence of events led them to sell him into slavery in Egypt. Today we jump almost to the end of his story — in between last week and this Joseph is framed on a charge of sexual misconduct with his boss’s wife, thrown into prison, makes use of his skill as an interpreter of dreams to get out of prison, and more than that, to be raised to a position of high power in Pharaoh’s kingdom. And he uses that power to store up supplies of food for the world-wide famine foretold in Pharaoh’s dreams — a pair of dreams that Joseph is able to interpret as a warning from God that a famine will strike the whole world.

When his brothers arrive, Joseph takes the time to indulge in a bit of payback: in the previous chapter — for they have come to Egypt to beg for food, for the famine is indeed world-wide, but have failed to recognize Joseph as their brother. This gives him an opportunity to play a few mean tricks on them — which, of course, they fully deserve. After that payback he finally chooses to reveal himself to them, in large part because he wants to see his elderly father again, and he knows that the famine is only just beginning and will get much worse. And the lesson he derives from this, is that even though his brothers did a truly terrible thing to him — he now sees that this was God’s way of working; God has taken this very bad thing and made a good thing come out of it. As Joseph would say in the last chapter of Genesis, “Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good, in order to preserve a numerous people.” So it is that a good thing came out of the actions of bad people; and in the end, even good things for those bad people.

+ + +

And that’s the hard part for us to understand. We expect wrongdoers to get punished, not rewarded. We expect bad things to happen to bad people. The problem is that this is a point of view that puts us in the place of God; it puts us in the position of judging others, deciding that they are bad and deserve punishment. And it isn’t really a question of being right or not — that is, it may be perfectly true that the people who we think are be bad are bad, and do deserve to be punished. The problem is that in placing ourselves in the judge’s seat and condemning others, even if we are right, we forget that we too are guilty — perhaps at times even more than those we condemn.

This is one of the hardest teachings of Jesus to wrap our heads around. How many Christian leaders seem to think that their primary task is telling other people how bad they are? How easy it is to forget that a central teaching of the Christian faith is, Do not judge! How easy it is for Christian disciples to consider themselves equal to their master, competent to judge — and even worse, getting on a high horse to decide who is a worthy recipient of God’s mercy.

We see them do that in today’s gospel reading. A Gentile woman, a Canaanite, approaches Jesus and begs him to cast a demon out of her daughter. And notice that at first Jesus says nothing. Matthew goes out of his way to include that detail: Jesus doesn’t answer her at all. He keeps silent. Is he waiting to see what the disciples will do? Will they intercede and join in her plea for mercy? Will they say to Jesus, Look at this poor woman? Jesus doesn’t have to wait long because they very quickly urge him to send her away because she keeps shouting after them. And at first he confirms their action — for he tells them that he was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel. Even when the woman comes and kneels before him, and asks for help, he says that it isn’t right to take children’s food and throw it to dogs. But she insists that even the dogs get the scraps — and Jesus acknowledges her great faith and her daughter is healed instantly.

Just as Joseph puts his bad brothers through the ringer — framing them for theft and putting them in prison — before finally revealing himself to them and forgiving them; Jesus puts his disciples to the test, and gives the woman herself a hard time, before relenting and responding in mercy.

And mercy is the point, the point we often miss. Because God is judge, we tend to want him to act like a judge, particularly when we agree with the guilt of those who are accused. We want to see the judge hand down a hard sentence when other people are before the court. We want to see that hard sentence passed, and that the guilty are punished as they deserve — we want bad things to happen to bad people. And so we want to see God act as a stern judge.

Except when we are the ones standing before him. That’s when we want God to be merciful. The problem is that God doesn’t change — God is always just and always merciful. God is always bringing good out of bad. Joseph’s brothers do a terrible thing in trying to kill him and getting him sold into slavery. But God uses that very action to put Joseph in the position to save the lives not only of his brothers but of countless other people, as God gives him the wisdom to understand Pharaoh’s dreams, and to store away enough food to last through the seven-year famine that will afflict the whole world.

Jesus teaches his disciples a lesson about mercy in this gospel we heard today — a lesson about mercy and faith. For recall how just last week he chided Peter, when he sank in the water he tried to walk on: “You of little faith!” Yet here — in front of Peter and the other disciples — he praises this Canaanite woman, this Gentile pagan, without doubt a worshiper of false and foreign gods, he praises her and gives honor to her “great faith.” Imagine how Peter felt at that moment!

Jesus answers the prayer of one who is not among his lost sheep, who is not his child, who is no better than a dog in the household. He does good for one who deserves no good — not because she deserves it but because he is merciful. Mercy is what it is all about. All, as St Paul said, are under disobedience, so that God can show mercy to all. It’s all God’s mercy, grace, and favor that saves us. I’m reminded of a quote from Mark Twain: “When you get to heaven, you will have to leave your dog outside. Admission to Heaven is by favor. If it went by merit, you would stay out and your dog would come in.”

+ + +

In his letter to the Romans, Paul the apostle makes that point in big letters. All are placed under disobedience so that God may show mercy to all. There is none perfect, no not one; and yet God causes his sun to shine and the sweet rain to fall on the just and the unjust alike. God is a well of mercy that never stops flowing.

God may have seemed, Paul says, to have turned on his people, his chosen ones, the descendants of Joseph and his brothers, the people of Israel. But Paul insists that their disobedience is temporary and their punishment is temporary, for the very purpose of allowing the good news of salvation through Christ to be extended out beyond that Jewish household to those very Gentiles whom the Israelites think are no better than dogs, unworthy of salvation and doomed to destruction. God is showing mercy to the Gentiles and will do so for Israel in due time. Good things do happen to bad people: for God is merciful. God takes the twisted, broken mess of our lives, what we in our foolishness or our selfishness have spoiled or ruined, and God cleans us up, repairs us, restores us — redeems us.

There is a refrain in the Psalms: his mercy endures forever. Let us give thanks for that at all times — for his mercy endures forever; not seeking God’s judgment, for others or ourselves — for his mercy endures forever; but trusting in God’s mercy — for his mercy endures forever; that even the disobedient and the sinful will find redemption and release — for his mercy endures forever.+